The context in which we view a thing has a great influence on our perception of it. It is a great influence on our perception of Zen.When we first learn about something it's with our senses and we know all too well that they can mislead, tricking us to believe that things are one way when they are, in fact, another. We enter a Buddhist temple and see a giant statue of the Buddha, smell the fine aroma of incense, and hear the chanting of monks: we are enveloped in a sensory extravaganza of delight, or awe, or bewilderment, or confusion, depending on our predisposition to, or attitude toward, the experience.

Before I discovered my Self I gauged every thing by something else. Now I know to gauge everything only by what it is in relation to its Self." - Anonymous

>The context in which we view a thing has a great influence on our perception of it. It is a great influence on our perception of Zen.When we first learn about something it's with our senses and we know all too well that they can mislead, tricking us to believe that things are one way when they are, in fact, another. We enter a Buddhist temple and see a giant statue of the Buddha, smell the fine aroma of incense, and hear the chanting of monks: we are enveloped in a sensory extravaganza of delight, or awe, or bewilderment, or confusion, depending on our predisposition to, or attitude toward, the experience. Zen always exists within a context, as does everything, yet the very nature of Zen allows it to adapt to an infinite variety of external contexts because, by itself, it is without context. The pure context of Zen is our Inner Being - our life force -- the essence of which is devoid of subjective sensory experience. It is a metaphysical context, and as such, it is also an indescribable one.

Yet it's the sensory and mental experiences of our lives, and specifically, of our encounters with Buddhist teachers, statuary, literature, etc., that give us an impression of what Zen is. To avoid being misled, it's important to remember that these are all merely impressions of Zen, not what Zen is.

A culture in which Zen Buddhism has established deep roots has no problem with defining the context of Zen and, in fact, its native adherents often view that context as synonymous with Zen itself. We see this exemplified by the many customs and regimens an aspirant is told to adhere to and obey - bowing, chanting, styles of sitting and walking meditation, food regulations, garment regulations, social protocols, and the like - before being privileged to gain Zen training. The challenge for such cultures is that they can easily, if involuntarily, lead a seeker into the trap of mistaking the finger for the moon - mistaking outward impressions for spiritual understanding: mistaking religious decorum for transcendent wisdom.

Yet, as far as I know, nobody has figured out a way to introduce Zen to a newcomer without surrounding it within some kind of context. We can say that the general context has always been Buddhism - but the specific context has varied tremendously from country to country, culture to culture, and teacher to teacher. A culture new to Buddhism, such as our Western one, faces the extreme challenge of creating a sustainable context for Zen to exist within.

In the West, Chan Buddhism is most often nestled within Buddhist temples founded and managed by peoples of non-Western origins. Culture and language differences form natural barriers for Westerners. Some Asian Buddhists perceive Westerners as "unable to grasp" Buddhism in general and Zen in particular, possibly because they feel unable to connect with Westerners socially and linguistically. In response to this attitude, there are many Westerners who perceive Asian Buddhist teachers as the only ones who can "get it." Both groups tend to identify the context of Zen with the Asian culture itself.

In order to hurdle this artificial perception of Zen Buddhism, we not only need to create a new context in which we learn about and "practice" Zen, we need to recognize that Zen is not implicitly bound to Asian cultures. It belongs to no single group of people, to no single culture or country. It is defined only by the context in which we, individually and uniquely, experience it.

Where does this leave us? It leaves us with the essential ingredient of Zen - ourselves. It leaves us with our own pursuit of the divine through willful effort, devotion, humility, and self-sacrifice.

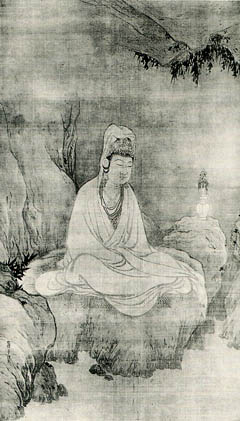

Does this mean we, as Westerners, are free to throw away the cosmetic structures of traditional Asian Buddhism - chants, malas, sutras, statuary, incense, rules, etc.? No, quite the opposite. It means we embrace it all, recognizing these things as valuable stepping-stones on the spiritual path. They may or may not be the same stones we tread, but as long as they are used, they serve a valuable purpose. Zen is an extraordinarily difficult discipline to undertake, and it's rare to find an individual who can not benefit from the fragrant smell of incense, the serene presence of Buddha statuary, the deep reverberations of chanting - all these things can help propel us into that state of spiritual awe - that numinous state that we thrill to encounter every time. A mala, or rosary, is something we can carry with us in our daily lives as a permanent reminder to "be present" in ourselves. Such contextual surface features are important because they lead us toward an inner life.

And, simply put, that's where we want to be. That is the pure context of Zen.